Omicron is a variant of SARS-CoV-2 that has caused a series of cases in South Africa and is currently spreading around the world. Similar to previous variants that have attracted attention, this mutation has enhanced transmission and resistance to vaccines. In the beginning, the number of daily cases in South Africa was quite low, but then it rose sharply from 273 on November 16 to more than 1,200 on November 25. More than 80% of cases occurred in the northern province of Gauteng, exactly where the first batch of cases was found. On November 26, Belgium detected Europe’s first confirmed case of the new variant, and by November 29, cases had been reported in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Portugal, and Italy. In addition, cases have been reported in Botswana, Hong Kong, Canada, and Australia.

Lawrence Young, a virologist and professor of molecular oncology at the Warwick Medical School, said, “This new variant of the covid-19 virus is very worrying. This variant carries some changes we’ve seen previously in other variants but never all together in one virus. It also has new mutations that we have never seen before.” In total, the genome of this variant has about 50 mutations, of which there are more than 30 found in the spike protein. Spike protein is the part that interacts with human cells before cell entry and is also the main target of current vaccines. David Matthews, a professor of virology at the University of Bristol, said “this variant might be better at spreading than the delta variant.” Wendy Barclay, Head of the G2P-UK National Virology Alliance and research chair in virology at Imperial College London, said that although current vaccines proved to be less effective against omicron, they may still provide some protection, and she urged the public to take up all vaccine shots offered.

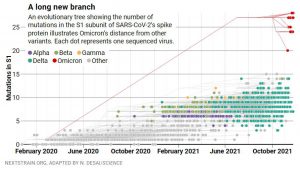

Emma Hodcroft, a virologist at the University of Bern, stated that “Omicron is so different from the millions of SARS-CoV-2 genome that have been publicly shared that pinpointing its closest relative is difficult.” It likely diverged early from other strains, she says. “I would say it goes back to mid-2020.” Omicron was obviously not developed from one of the early-focused variants, such as Alpha or Delta. This raises the question of how Omicron’s predecessors lurked for more than a year.

Scientists have given 3 possible explanations:

1. The virus may spread and evolve in people with little surveillance and sequencing.

2. It may evolve in chronically infected COVID-19 patients.

3. It may have evolved in non-human species, and recently spread back to humans from non-human species.

Christian Drosten, a virologist at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin, supports the first possibility. “I assume this evolved not in South Africa, where a lot of sequencing is going on, but somewhere else in southern Africa during the winter wave,” he said. “There were a lot of infections going on for a long time and for this kind of virus to evolve you really need a huge evolutionary pressure.”

But Andrew Rambaut of the University of Edinburgh cannot understand how the virus has been hidden in a group of people for so long. He said, “I’m not sure there’s really anywhere in the world that is isolated enough for this sort of virus to transmit for that length of time without it emerging in various places.”

On the contrary, Rambaut and others suggested that the virus is most likely to develop in a chronically infected COVID-19 patient, who may be a person whose immune response is impaired by another disease or medication. When Alpha was first discovered in late 2020, the variant appeared to have acquired many mutations at the same time, which led the researchers to hypothesize a chronic infection. This idea is supported by the sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 samples from some chronically infected patients.

“I think the evidence to support it is getting stronger,” said Richard Lessers, an infectious disease researcher at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In one case Lesells and his colleagues described in a preprint, a young South African woman who was infected with the uncontrolled HIV virus and carried SARS-CoV-2 for more than 6 months. The virus has accumulated many of the same changes seen in the worrying variants, and this pattern also appeared in another patient with SARS-Cov-2 infection that lasted longer. In order to prevent a possible source of mutation in the future, Lessells said, “What we need to do is to close the gap in the HIV treatment cascade. So we need to get everyone diagnosed, we need to get everybody on to treatment, and we need to get those that are currently on ineffective treatment on to effective treatment regimens.”

But Drosten said that experience with chronic influenza infections and other viruses in immunosuppressed patients is contrary to Omicron’s hypothesis. It is true that mutations that evade the immune system do develop in these people, but they will bring about many other changes that prevent them from spreading from person to person. “These viruses have very low fitness out in the real world.” This is because over time, the mutations that allow the virus to survive in a person may be different from those needed to best spread from one person to the next.

Jessica Metcalf, an evolutionary biologist at the Berlin Institute for Advanced Study, is not sure whether SARS-CoV-2 is the case. “I think one reason that this virus has done so well is that better binding to ACE2 helps for both within-host spread and between-host spread.” For now, however, she agrees with Drosten The view that Omicron is likely to spread and evolve among hidden populations.

Some people think that the virus may have hidden in rodents or other animals, rather than humans, and therefore have experienced different evolutionary pressures and selected new mutations. “The genome is just so weird,” said Kristian Andersen, an infectious disease researcher at Scripps Research, pointing to its mutant mixture, many of which have never been seen in other variants before.

“It is interesting, just how crazily different it is,” said Mike Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Worobey pointed out that although he supports immunosuppressed people as a source of Omicron, 80% of the white-tailed deer sampled in Iowa from late November 2020 to early January 2021 carried SARS-CoV-2. “It does make me wonder if other species out there can become chronically infected, which would potentially provide this sort of selective pressure over time.”

Aris Katzourakis, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford, said that it is too early to rule out any theory about the origin of Omicron, but given the large number of human infections, he is skeptical of the situation in animals. “I’d start worrying about animal reservoirs more if we were succeeding in suppressing the virus, and then I could see it as somewhere it might hide.”

Many global health leaders have used the emergence of Omicron to focus the world’s attention on the huge gap between COVID-19 vaccinations in rich and poor countries. In a speech at the World Health Assembly on November 29, Richard Hatchett, head of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, said that the low vaccine coverage in South Africa and Botswana “provided a fertile environment” for the evolution of the variant. He said, “The global inequity that has characterized the global response has now come home to roost.”

However, some scientists stated that there is little evidence to support this claim. “The idea that if we had vaccinated more in Africa, we wouldn’t have this: I’d like that to be true, but we have literally no way of knowing,” Katzourakis said. For now, the lesson to be learned from Omicron is as unknown as its origin.

In summary, so far scientists have not been able to reach a unanimous conclusion. From the data point of view, the risk of Omicron spreading further is extremely high, but whether it causes a mild infection or not may vary from person to person.

Reference:

- Kupferschmidt Kai, Where did ‘weird’ Omicron come from?[J].Science, 2021, 374: 1179.

- Tanne Janice Hopkins, Covid 19: Omicron is a cause for concern, not panic, says US president.[J].BMJ, 2021, 375: n2956.

- Graham Flora, Daily briefing: Omicron coronavirus variant puts scientists on alert.[J].Nature, 2021.